Field Notes from

Field Notes from

a Catastrophe

Man, Nature and

Climate Change

Elizabeth Kolbert

(Bloomsbury Publishing, 194pp, $22.95)

The choice of this �holiday book� was strictly a matter of �inconvenient timing.� I was in the process of perusing the gift titles promoted by the sea of large and small presses for this month�s review. Taking a break, I picked up the November 20, 2006 issue of The New Yorker and was stopped in my page-flipping enjoyment of the cartoons by a magnetically beautiful black and white photograph of a deeply angry ocean. Glaring out from an inky storm cloud was the title of the article �The Darkening Sea--What carbon emissions are doing to the ocean� by Elizabeth Kolbert, an only vaguely familiar name to me.

Kolbert was a reporter for the New York Times for fourteen years before she became a staff writer covering politics for The New Yorker. Field Notes from a Catastrophe is based on previous New Yorker articles, which I had apparently missed. She is also the mother of three sons to whom Field Notes, only her second book is dedicated. Her current New Yorker article on the acidification of the oceans was so riveting that I picked up the book the same day. Not your typical warm and fuzzy holiday title, I know. Nevertheless, it is my one and only suggestion for everyone on your gift list that can read. It�s is a little stealth volume which really packs a wallop.

Divided into two parts �Nature� and �Man.� Kolbert is the reporter on the front line. She goes where the �action� is, interviewing affected inhabitants and the scientists who measure that �action.� Shishmaref, Alaska for instance, is a village on an island five miles off the coast of the Seward Peninsula. The site has been populated for several centuries by Inupiats (591 at last count). Traditionally, they hunted sea mammals by driving dogsleds, later snowmobiles, across the sea ice to open water�20 miles away. Today the ice extends less than ten miles and is too mushy to traverse. The ice also freezes later in the year leaving the village vulnerable to ravaging storms and accompanying high seas. The solution proposed by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers is to physically move the village to an equally inaccessible site on the mainland at a cost of $180 million dollars.

A second trip to Alaska took Kolbert into the interior of the state with a University of Alaska geophysicist who monitors permafrost. Defined as ground that stays frozen for more than two years, permafrost serves as a record of long-term temperature trends as well as a repository for green house gasses. Most Alaskan permafrost has been in place for 120,000 years. In some parts of the state, however, permafrost has warmed nearly six degrees since the 1980s causing chasm-like ruptures on the surface. The �hottest� real estate is now permafrost-free due to potential destruction caused by the melt process.

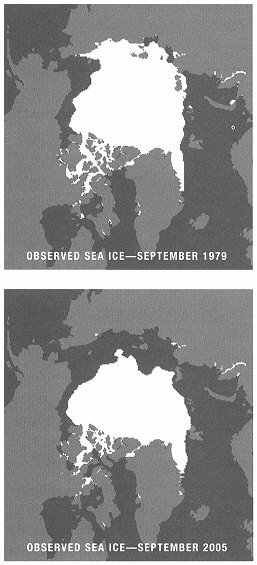

The next stop for the intrepid reporter is Greenland, specifically to Swiss Camp, a research station on a platform drilled into the ice sheet, which covers more than 80% of the 840,000 square mile island. Ice cores taken by the scientists at the station provide a continuous temperature record. Other measurements record glacial elevation and rate of movement of the constantly shifting ice.

The consequences of glacial melt are multi-faceted and far-reaching. Kolbert explains how temperature, weight and salinity of the waters on our planet drive world climate. She does so with such a visionary clarity building on a combination of thoroughly understandable details that she leads the reader to a flash of understanding that he/she believes for a moment he�s/she�s the genius.

But it�s not just the scientists who are witnessing and documenting the increasingly rapid climate change. When Kolbert visits Iceland, she meets the members of the Icelandic Glaciological Society, all of who are civilian volunteers. Every fall after the summer melt, the country�s citizens have surveyed and measured the size of their glaciers. Kolbert�s guide, Oddur Sigurdsson told her that the glacier he monitors has shrunk 1100 feet in the last decade. scientists who are witnessing and documenting the increasingly rapid climate change. When Kolbert visits Iceland, she meets the members of the Icelandic Glaciological Society, all of who are civilian volunteers. Every fall after the summer melt, the country�s citizens have surveyed and measured the size of their glaciers. Kolbert�s guide, Oddur Sigurdsson told her that the glacier he monitors has shrunk 1100 feet in the last decade.

As if the front line researchers at the top of the world have not lent enough weight to the argument for the existence of global warming, Kolbert travels to England and talks with a biologist who tracks butterfly ranges (which are moving ever northward) and to the Monteverde Cloud Forest in Costa Rica which is receding upwards drying up life-supporting habitats as it retreats.

In the second section of Field Notes Kolbert looks at the effects of climate change on humanity, both from historical and current perspectives. She cites the world�s first empire located between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers some 4300 years ago as well as the Classic Mayan civilization�both annihilated by prolonged drought. These civilizations were unable to predict such changes and therefore fell victim to them. �The climate shifts predicated for the coming century, by contrast, are attributable to forces whose causes we know and whose magnitude we will determine,� she says.

She eases into her conclusion with the interim solutions of one of the most densely populated communities vulnerable to warming trends and rising waters�the Dutch who are building �amphibious� homes and evacuating low areas near deltas to �give the rivers room.�

A tense description of the current indifferent activities of countries like the U.S. and China which BAU (business as usual)is countered by an oddly optimistic outline of the climate modeling research being conducted at The Goddard Institute for Space Studies led by its outspoken director, James Hansen. Although dire findings are largely ignored or undermined by the U.S. government and the corporations it represents, solutions abound in the scientific community. Hopeful scenarios exist.

Multi-layered effort and worldwide cooperation to curb the release of carbon and its system-wide consequences could succeed in reversing the trend. As she has demonstrated throughout her book, the situation is a matter of scale. �The feedbacks have been identified in the climate system that take small changes and amplify them into much larger forces. Perhaps the most unpredictable feedback of all is the human one,� she says. Kolbert argues for a global response but concludes bleakly that our present course is toward self-destruction in spite of our technological sophistication.

The power of this book is like the problem the author describes�it is a matter of scale�the elements of plain language, engagingly personal anecdotal experience combined with gloriously simple explanations of both process and problems make this possibly the most persuasive discussion of the subject to date. Her tone is neither shrill not heavy-handed, rather it is almost eerily matter-of-fact.

But be warned, when you finish this deceptively slight volume, you may be in a temporary state of mourning. On reflection, however, you will be energized and exhilarated. The opportunity to be so profoundly educated in such a few pages may just turn the tide. Make this book your only gift this season.

|